Project implementation: Chile

Project development: Chile

The action-research project "Errando se Aprende" (Errando se Aprende) is located in Reñaca Alto Sur (Viña del Mar, Chile), a region marked by housing insecurity, urban exclusion, and vulnerability to wildfires. The Huasco ravine, historically seen as a boundary, has great potential to become a corridor for community and ecological life. The climate crisis and the 2024 fires have heightened the urgency of rethinking this space, highlighting the need for infrastructure capable of protecting the population and ecosystem.

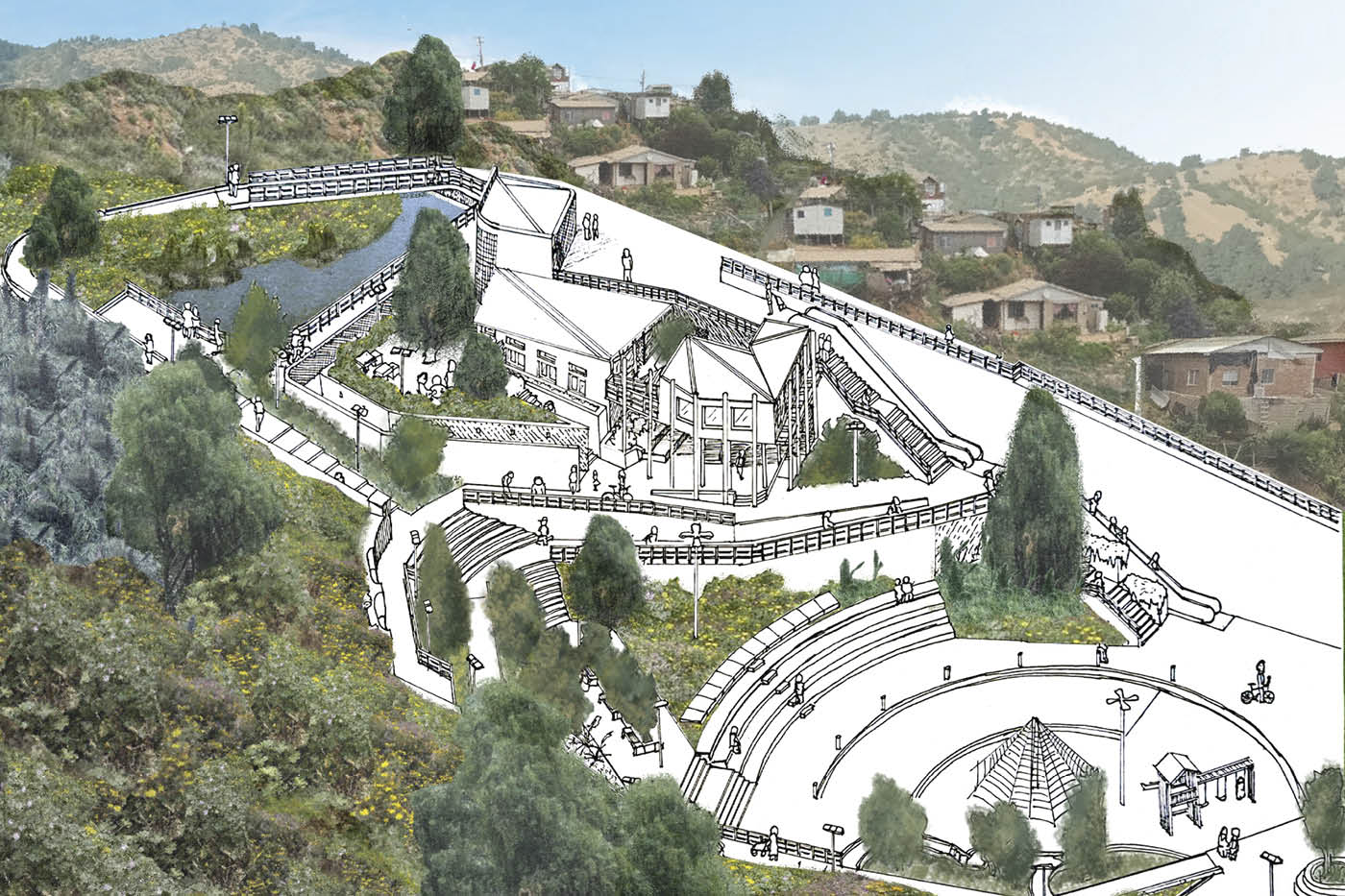

In this context, a collective masterplan was developed, built through participatory workshops, tours, and community observations. The strategy views the favela as an inter-neighborhood park, connecting villages through green infrastructure, community facilities, and fire protection corridors. More than simply designing spaces, the goal was to shift perspectives: understanding the encampment not just as an informal settlement, but as a territory with a right to the city and a sustainable future.

Based on this, a Community Meeting Center was proposed at a strategic location in the favela. The building connects the inter-neighborhood park to everyday spaces—a cafeteria, playroom, and offices. It's not a standalone facility, but the embodiment of the masterplan as a space for gathering, cohesion, and mutual care, capable of strengthening community networks.

The project also introduces a new type of water reservoirs, designed as a prototype for community infrastructure. They serve a dual purpose: storing gray water for daily use and forming a fire protection network in areas where fire is a constant threat. This creates a new field of basic infrastructure for camps, combining safety, sustainability, and community care.

The choice of masonry responds to technical and social criteria. In a territory with difficult access and high exposure to fire, brick ensures resistance, permanence, and community ownership through self-management in construction. Materiality is also a pedagogical resource for learning and collective rooting.

The project demonstrates that architecture, beyond shelter, can activate processes of resilience and territorial justice. The favela, historically neglected, becomes the hub of a situated urbanism that connects nature, community, and the city. Even in contexts of extreme precariousness, it is possible to design infrastructures that are not palliatives, but triggers for social and environmental transformation.

More than an academic exercise, this is a research-action process that connects urban and architectural scales, moving from a collective masterplan to concrete community infrastructure. This process reveals the project's purpose: not to impose external design, but to collectively construct responses that combine heritage memory, shared care, and new ways of living in times of climate crisis.